by MAC

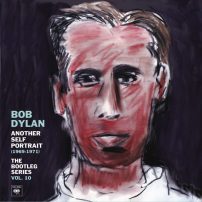

“Self Portrait” has always been one of Dylan’s most inscrutable albums, which is saying a lot, as Dylan is notoriouslu difficult to pin-down to any one pre-defined image that his rapid fans (of which I happily count myself as one of them) or his famously troubled relationship with the rock press. Released in 1970, “Self Portrait” follows the very brief 1969 LP “Nashville Skyline”, itself something of a head-scratcher for Dylan followers in the late 1960s. And make no mistake, the famed opening salvo of Greil Marcus’s famous “Rolling Stone” review “What is this s–?” was by far the general consensus of “Self Portrait”, with some going so far as to suggest that the breakup of The Beatles was the end of the 1960s, and Self Portrait was the end of Bob Dylan, effectively ending the two most potent musical forces in the 1960s counterculture.

The release itself is in two forms: a two disk set with 35 tracks, and a four disk set with the complete Isle of Wight on a third disk and a remastered version of the original album on the fourth disk. The four disk set is, like “The Bootleg Series Vol 8”, cost prohibitive to own. The record comprises of “Nashville Skyline” outtakes, “New Morning” Outtakes, the long known but uncirculating “Only a Hobo” from the “Greatest Hits Vol III” sessions, and obviously “Self Portrait”, with the lion share’s going to SP. Despite its title, there is a Basement Tapes recording of “Minstrel Boy” from 1967 included, which from a recording sessions perspective is the single biggest revelation yet unveiled in “The Bootleg Series” – NO ONE knew that “Minstrel Boy” originated during the Basement Tapes era, let alone that a BT recording even existed! One disappointing fact is that some of the Isle of Wight performances appear on both Disk 2 and Disk 3 (if you get the deluxe version of this set) which creates unnecessary duplication of material.

Hyperbole aside, So what does “Another Self Portrait” tell us about the original “Self Portrait”? Simple. “Self Portrait” should have been far richer than its detractors will allow for, that it has a sever identity crisis, and that, of all Dylan’s albums, it is a key to understanding and “unlocking” the “enigma” of who Dylan actually is (the answer – a musical chamaeleon, a cultural transmitter of pre-rock American musical forms who inputs little to none of his own identity in his work, only excepting his vast encyclopedic love of pre-rock traditions).

So, what is that identity crisis? Answer: “Self Portrait” falls somewhere in between a legitimate follow-up to “Nashville Skyline”, a slight country album, and a wilfully perverse screw-you to his fans. This tension between a legitimate artistic statement and a “Leave me alone attitude!” makes the original release so fascinating. Listening to “Another Self Portrait” is revelatory – it’s obvious that, listening to these outtakes, had the album been sequenced properly, we could have had a fantastic, cohesive Dylan album that, while radically from his 1960s’ work, would have shown just how masterfully he was at interperting other people’s work. “Another Self Portrait” also shows that, at least originally, the project began as a serious album, and not a red herring to throw off his followers.

As is typical with so much of Dylan’s output, the outtakes say as much (and in the case of Self Portrait, MORE) about a particular album as the songs that actually make the final product. There is simply no reasonable explanation as to why songs like “Thirsty Boots”, the stunning “Pretty Saro”, “Annie’s Going to Sing Her Song”, and “Railroad Bill” did not make the final cut. Dylan’s vocals are fantastic throughout; nuanced, compelling, hard-hitting.

Compare these tracks to what DID make the album: two versions of “Alberta” (itself a good song, but the takes aren’t really that different to merit the inclusion of both), two different versions of “In Search of Little Sadie” (though with quite different arrangements), a double tracked version of Dylan dueting with himself on Paul Simon’s “The Boxer”, which is so bad it almost sounds like Dylan’s doing a sendup of Simon, and four badly mixed, badly sounding Isle of Wight performances. Indeed, the live rendition of “Like a Rolling Stone” sounds like a parady of the masterful original, a gross reminder of just how far removed Dylan wanted to be from his adoring fan base. Songs like “Copper Kettle” and “Days of `49” show encouraging signs of what Dylan was up too.

“Another Self Portrait” also reveals that “Nashville Skyline”, “Self Portrait”, and “New Morning” (released a mere FOUR months after “Self Portrait”) is much more homogenous artistically than the critics would lead you to believe. The commonly accepted narrative in rock criticism is that Dylan quickly recorded “New Morning” after the disastrous reception to “Self Portrait”. “Another Self Portrait” reveals a different narrative however; there is little to differentiate the “New Morning” sessions from the “Self Portrait” sessions in either style or content, with the only main difference being Dylan began writing more original material during the latter sessions (much like he did with “The Basement Tapes”). However, it’s notable that seven of the nine covers from the 1973 “Dylan” album (which Dylan has disowned, and was released without his input as revenge by Columbia when he left for David Geffen’s newly formed Asylum Records) hail from the “New Morning” sessions, proving Dylan was just as interested as interpreting and playing other people’s music as he was performing his own.

So what makes “Self Portrait” so inscurtable? Well, first off, it’s discerning Dylan’s intent. What was he trying to do, or accomplish, with this double LP?

If you read Dylan’s various statements throughout the years, you will get conflicting reports. The most commonly accepted explanation (and one advocated by Greil Marcus in the liner notes) is Dylan was trying to “shed” his audience. Dylan himself said as much in a Rolling Stone interview from 1984.

” I wish these people would just forget about me. I wanna do something they can’t possibly like, they can’t relate to. They’ll see it, and they’ll listen, and they’ll say, ‘Well, let’s get on to the next person. He ain’t sayin’ it no more. He ain’t given’ us what we want,’ you know? They’ll go on to somebody else. But the whole idea backfired. Because the album went out there, and the people said, ‘This ain’t what we want,’ and they got more resentful. And then I did this portrait for the cover. I mean, there was no title for that album. I knew somebody who had some paints and a square canvas, and I did the cover up in about five minutes. And I said, ‘Well, I’m gonna call this album Self Portrait.'”

While it is impossible to speak to another person’s motivations fully and with equal authority to that person himself, I personally believe that this explanation is reducing the truth about “Self Portrait” to a much more limited capacity than it really was, at least in 1970. Looking back throughout the years, Dylan may have analyzed himself more and more and come up with the explanation he was trying to deal with his frustrations with his vampire fanbase (who he described in the same interview as “sucking the blood” from him), and that may very well be part of his motivation for recording of “Self Portrait”.

However, there was always some evidence (on both the album itself and contemporary interviews circa 1970) against that being the only reason why Dylan put out “Self Portrait”, and with “The Bootleg Series 10: Another Self Portrait”, that evidence has only grown exponentially. Despite what Dylan would later say, interviews given around 1970 carries far more weight, as Dylan himself was closer to the actual event. Like everyone else, as the years go back memories fade and we often forget what we were really thinking, or come up with alternate explanations. In a 1971 interview with notorious A. J. Weberman, who knew more about Dylan’s (literal) trash than Dylan’ probably did, Dylan defended the album, angrily blasting Greil Marcus. Robert Shelton asked Dylan in 1986 about Self Portrait, and, notably, he differed from his official reason of audience shedding: he said that songs like “Blue Moon” were an expression, and had someone like Elvis Presley or the Isley Brothers had released that album, then the response would have been much different.

Allen Ginsberg, who had known Dylan since the early 1960s, went on tour with him in 1975. A relevant quote from Bill Morgan’s biography of Ginsberg is one of the keys to unlocking the mystery of “Self Portrait”. “The more Allen thought about Dylan, the more he realised that he didn’t really know him at all, and he commented that he thought it was possible there was no “him” to know. He was beginning to think Dylan didn’t have a “self” at all”.

This concept of Dylan not having a “self”, albeit rather abstract and perhaps hard to define in a practical sense, to me brings intense illumination on not only this era of Dylan’s recording career (1969-1971), but to the entirety of his career in general. If you accept Ginsberg’s assertation that Dylan has no self, the title of “Self Portrait”, a double album of then contemporary covers and reimaginings of old folk songs, no longer has the smug ironical tone that some reviewers have mistakenly assigned to the project, but rather a deep truth about Dylan himself that has only been born out in subsequent years. And what is that truth?

Ginsberg was famous for recording his life in great detail, and reading through his works you get a real sense of his life, his personality, and who he was as a person and what he stood for and was concerned with. In contrast, Ezra Pound’s first major book of poetry was entitled “Personae”, where you never hear Pound’s own true voice, but rather a kaleidoscope of different voices and different masks. Even in “The Cantos”, other than Pound’s economic theories, you will learn far more about Pound’s sense of history than about his character and soul.

Likewise, Dylan has always been more a conglomeration of differing traditions than an original force, unique unto himself. The title “Self Portrait” was not meant to be ironic; Dylan finds his identity through his own synthesis of traditional, Americana music. While that may be a very broad claim to make, I am able to provide a good deal of evidence for such an assertation. While not one solitary piece of evidence can conclusively prove one way or the other that Dylan’s identity is not his own, the growing amount of evidence can be used in conjunction with each other that, quite convincingly, Dylan’s real identity is traditional music, and, with one notable exception, we have never been very close to who Dylan “really is”, because he really isn’t anyone.

Now, any hypothesis worth its salt should be able to accurately account for various, otherwise inscrutable facts and phenomena. The idea that Dylan doesn’t have a “self”, or, at least, use his music to express himself (far removed from “confessional” poets like Sylvia Plath, Robert Lowell, and Anne Sexton, and much more in tune with Pound and T. S. Eliot’s historical mode of thought) is quite a suitable framework to explain several otherwise odd facets of Dylan. It also explains his disdain for politics; Dylan was never political, despite what his followers wanted.

Before we examine the evidence, let’s first examine the one sore spot in the theory, and the closest Dylan has ever came to his own personal life: “Blood on the Tracks”, his 1975 album. Triggered by the disolution of his marriage to Sara Lowndes, the record is a heart-breaking divorce album. Yet even here, Dylan throws some curve balls. “Tangled Up In Blue” is far from a straight cry of pain, and is a jarring narrative that moves all over both time and space. Secondly, “Lily, Rosemary, and the Jack of Hearts” is a complex, lyrically demanding story straight out of the American west. However, excepting those two songs, the rest is an unusually straight reading of the pain that Dylan was going through. Jakob Dylan has said that album documented the dissolution of his parent’s divorce and failing marriage. The album was wrought in pain, and when an interviewer once asked Dylan about the album’s popularity, he said he did not understand why people enjoyed that much pain in their life.

What is more revealing, however, is what happened AFTER “Blood on the Tracks”. He recorded “Desire”, a deeply detached album emotionally (with the only exception being the last song, “Sara”) that delves into strong, lyrical story telling, especially coming off the heels of such an emotionally naked album like “BOTT”. Equally interesting, after “BOTT”, Dylan wrote several songs that were as emotionally intense as its predecessor but would not record them, electing instead to go with “Desire”. “BOTT” is far more an anomaly in Dylan’s career than anything else he has put out, with the closest equivilant being “Time Out of Mind”, another emotionally charged, deeply painful album. (I always felt TOOM was BOTT aged twenty two years).

First off is examining Dylan’s career in its entirety. The early 1960s has Dylan going through his troubadour, Woody Guthrie phase and political protesting; the mid 1960s’ moving through surreal lyrical work which is heavily indebted to Beat literature and French symbolists; the late 1960s tapping into that “Old Weird America” as evidenced on “The Basement Tapes” (which, notably, the majority of which is still commercially unavailable), and then turning out a brief country album with the opening track being a rather off-kilter duet with Johnny Cash. Even “John Wesley Harding” sounds much more an aural history of the United States post Civil-War, taping into the vast mythos of the American West, than ever revealing a single thing about who Dylan is as a person.

Post “Self Portrait” (which for reasons of space I won’t elaborate too greatly), we have the travelogue album of “Desire” and the incredibly strange, wilfuly obtuse “Street-Legal”. In the 1980s, he went through a career crisis, with several listless albums, often blocking release of superior songs on these admittedly drab albums (with the most famous example being “Blind Willie McTell” from “Infidels”, itself one of the stronger albums released during this period). According to “Chronicles”, in 1988, after a disastrous tour with the Grateful Dead, he realised he was not connecting with his music anymore, and had a personal revelation on how he needed to play and commenced with the Never Ending Tour, which proved to be a true turning point.

In the 1990s, after two folk albums, he released “Time Out of Mind”, which Dylan described as a deliberate attempt to make an old-time folky record, like the songs he would listen too back in the 1950s. Every subsequent album (2001’s “Love and Theft”, 2006’s “Modern Times”, 2009’s “Together Through Life”, and 2012’s “Tempest”), Dylan plays with pre-rock, old timey musical forms, each deeply rooted in the American musical body of work from the late 19th/early 20th century. Listening to his work, never once do you feel like you’re are truly getting to know Dylan intimately as a person (except fro TOOM, the emotional successor to BOTT); however, you do come away with a much deeper understanding of the cultural heritage of Americana music.

We also have the Christian trilogy, which may very well be the closest we get to Dylan as an actual person; religious themes have always ran deeply through his work, far more deeply and important to him than being a mere superficial synthesis of his traditional interpretations of pre-rock music.

In 1997, Dylan even said the following: “Here’s the thing with me and the religious thing. This is the flat-out truth: I find the religiosity and philosophy in the music. I don’t find it anywhere else. Songs like “Let Me Rest on a Peaceful Mountain” or “I Saw the Light”–that’s my religion. I don’t adhere to rabbis, preachers, evangelists, all of that. I’ve learned more from the songs than I’ve learned from any of this kind of entity. The songs are my lexicon. I believe the songs.” In promotion for the 2009 “Christmas in the Heart” LP, he told interviewer Bill Flannagan he was a true believer when talking about “O Little Town of Bethlehem.”

I think that, stepping out further from just religious concerns, this quote, in context with everything else, shows us just how important the music of “The Bootleg Series 10” truly is to Dylan. In an outtake version of “Political World” from 1989’s “Oh Mercy”, Dylan sings the lines (deleted in the final released version) that there are woman, wine, and songs, but without the songs you won’t get far in this world, which is one of the most revealing lines he ever wrote. Likewise, the title of his panned movie “Masked and Anonymous”, accurately describes Dylan himself, moving through life, inscurtable, unknowable.

Marcus said “I once said I’d buy an album of Dylan breathing heavily. I still would. But not an album of Dylan breathing softly. Ginsberg said in Scorcess’s documentary “No Direction Home”: “He had become at one with, or became identical with, his breath. Dylan had become a column of air so to speak, where his total physical and mental focus was this single breath coming out of his body. He had found a way in public to be almost like a shaman with all of his intelligence and consciousness focused on his breath.” If anything, “Self Portrait” shows Dylan mastering the art of the Buddhist breath.

I always thought, upon hearing Dylan was releasing a bootleg installment on “Self Portrait”, that it was an incredibly strange choice, given how much everyone always hated the record (especiallt with the rumoured super-fan dream choice of a “Blonde on Blonde” installment). Listening now, though, I understand.

So, what does this all admittedly long discussion of Dylan’s career and music (hard to succinctly compress for an Amazon review) mean for “Another Self Portrait”? Simply this: “Another Self Portrait”, appropriately enough, is probably the single most revealing release Dylan has issued, which is quite appropriate given its title.

Decades ago, Dylan gave us the key to who he was as an artist, and we resented him. Now, so many years later, we find Dylan was right after all – he is a mirror of Americana Music. As a critic once said, Dylan has “vanished into a folk tradition by his own making”. Vanish, though, is not the right word. The correct term would be “Homecoming”

.

You must be logged in to post a comment.